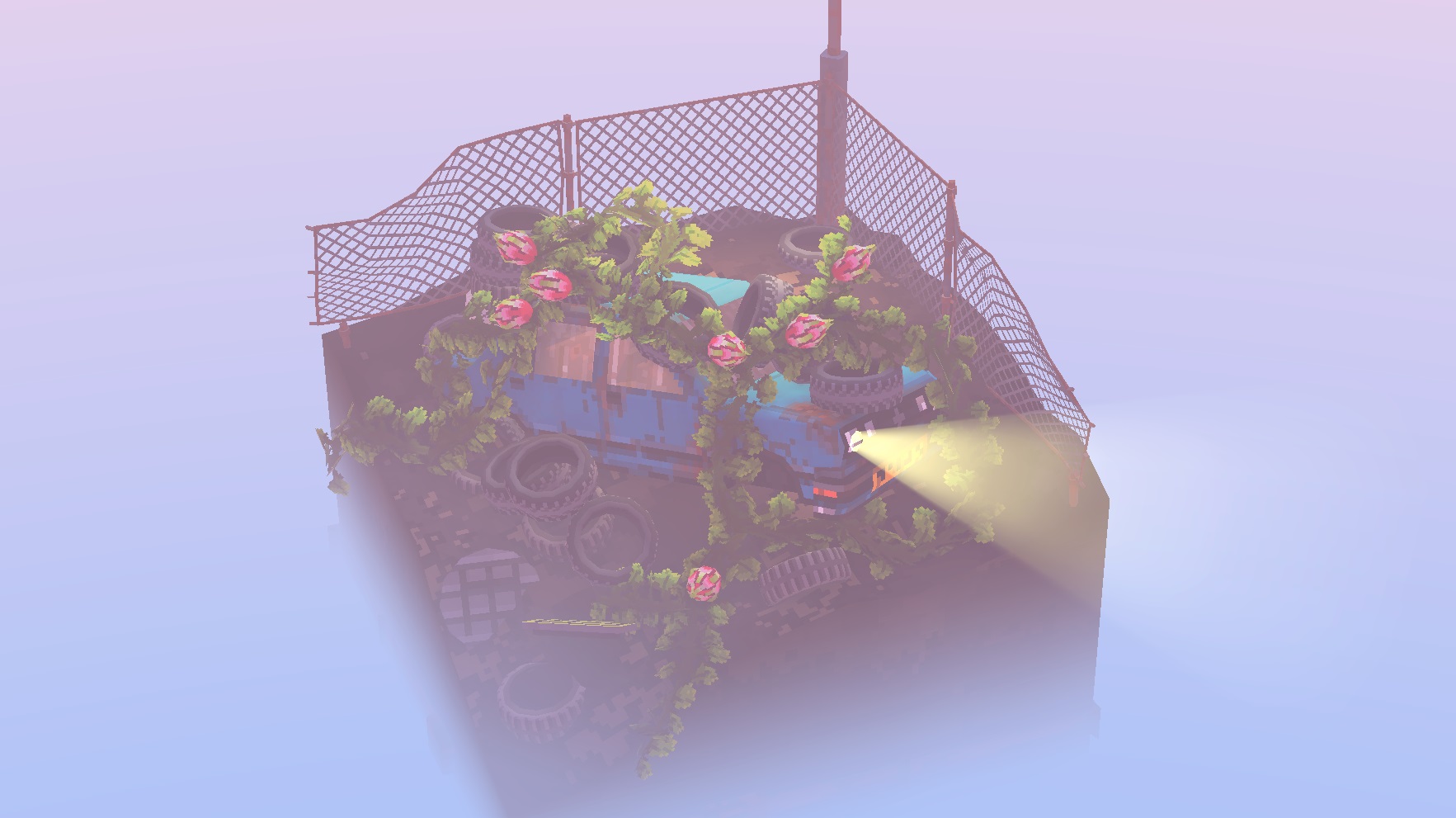

The reticle that appears on the ground seems to have a mind of its own, disappearing and reappearing depending on the stuff already laying around. But I could never quite be sure where I was putting items. You use the trigger buttons to zoom and shrink the scene, the R1 and L1 buttons to spin items, and the A button to place things. Overall, the controls feel clunky and imprecise. The chainsaw is a microcosm for another issue I had with Cloud Garden. A few other tools are provided – a vacuum allows you to suck up blooms when there are so many that you don’t want to click them one by one to harvest them, and an unusable chainsaw lets you hack back unwieldy growth, though I have no idea why you would ever want to do that. I watched the meter tick up and down between 89% and 92% yesterday afternoon while I sat and did nothing but move a suitcase two inches back and forth. Plant those seeds, lay more trash, grow more plants, until the game decides that you are done and moves you on to the next diorama.Ī little meter with a percentage in it tells you how close you are to completing your current project, though it all seems a little arbitrary. Once they bloom, the player can collect the flowers to create more seeds. The game provides a jumble of garbage to the player, anything from suitcases and backpacks to street signs to rusted out cars, which can be selected item by item and dropped near (but not on) the plants, which causes them to flourish and bloom. The seeds sprout a little when planted, but the real way to get them to grow is to lay down trash near them. Different seed types can be planted in different places some can be plopped right into the dirt, whereas others thrive when draped from structures. The player starts with a couple of seed types at their disposal, though the game quickly provides more. Players have two primary ways to interact with the world they can plant seeds, or they can lay down junk. It’s fun to rotate them around the first time you see them, taking in the little details. The dioramas are really quite cool, with a dreamy, hazy quality to them. Street signs, abandoned vehicles, and highway overpasses seem to make up the primary motifs at work here. The little slices of land in Cloud Gardens are occupied now only by birds. Either way, people used to preside here, and they clearly don’t anymore.

Hell, it could just be the parking lot at an old factory. Players start with a small pixel-art diorama depicting a tiny sliver of a post-apocalyptic world. The core loop of Cloud Gardens is simple.

But as time went on and I got further into the game, I felt myself wondering more and more about just what I was supposed to be doing. I’m not the sort of player that needs a huge narrative thrust to push me forward through a game, so I was excited for Cloud Gardens. Yeah, that’s what people think they want.īut what if a game commits to these design rules so stringently that the game passes through some hazy barrier of comprehension and becomes obtuse? Can a game attempt to show (rather than tell) to such an extent that the player is left bewildered, no matter how simple the core mechanics are? I’m not certain, but I do believe that Cloud Gardens – as simple as the core gameplay loop is - comes close that mystical realm of unknowable gameplay.Ĭloud Gardens is one of those “chill experience” games, almost more of a toy than a game. Don’t stop the action in the game to teach me which buttons to tap – just show me a simple HUD and let me figure it out. Avoid exposition when a story can be told environmentally. Don’t rely on tutorials when you can design things in such a way that a player can learn by doing. “Don’t tell me, show me.” You hear the refrain over and over again in game criticism.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)